Health Policy, Black Mothers & Babies, and America

This week NYT reported the stark reality for moms and babies in the US: being a mom or baby of African American descent almost doubles your risk of death, regardless of income!

Read time - 5 mins

This week NYT reported the stark reality for moms and babies in the US: being a mom or a newborn of African American descent almost doubles your risk of death, regardless of income!

What is the summary of the study report?

The study by Kate Kennedy-Moulton, Sarah Miller, Petra Persson, Maya Rossin-Slater, Laura Wherry, and Gloria Aldana found

“infant and maternal health in Black families at the top of the income distribution is markedly worse than that of white families at the bottom of the income distribution.”

The study goes on to compare CA and Sweden - why CA — because CA has one of the nation’s most progressive coverage of post-partum care for mothers. It is the closest US could compare to Sweden’s coverage of post-partum care.

Sweden offers:

“equitable access to healthcare both throughout the life cycle and at the time of pregnancy and childbirth, as well as social and economic aspects of the postpartum environment such as universal access to paid family leave” (Kennedy-Moulton et al)

“even relatively disadvantaged infants in Sweden—those born to immigrant mothers—experience lower LBW [low birth weight] and preterm birth rates at all points of the income distribution when compared to infants of both US-born and foreign-born mothers in California”

“we benchmark the health gradients in California to those in Sweden, finding that infant and maternal health is worse in California than in Sweden for most outcomes throughout the entire income distribution.”

Let me say this another way: in Sweden, an immigrant mother has better birth outcomes than a Black mother, born in the US, with average or above-average income.

This study helps us lay to rest the argument once and for all: economic income is a small factor in the scope of the high incidence of maternal mortality in the US.

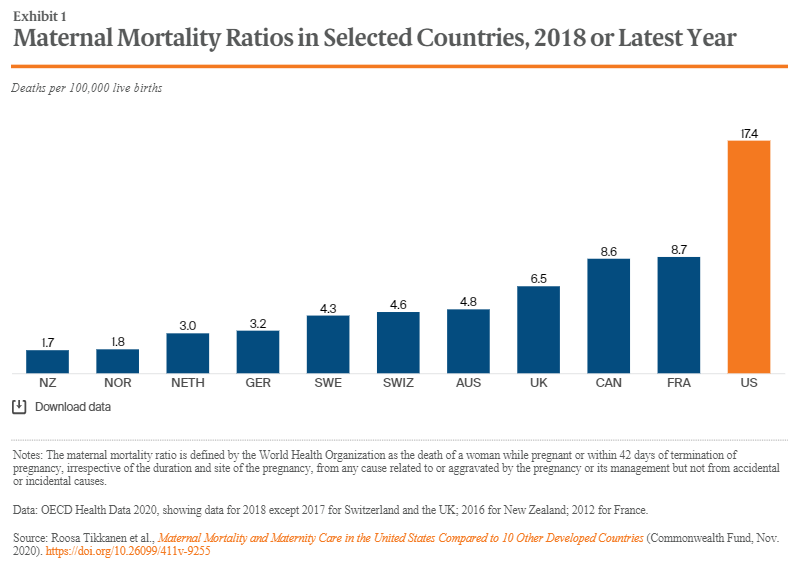

When compared to other “peer countries” US performance is very very poor.

Is the US really performing poorly on maternal mortality?

Yes. It is. It is abysmal.

If not socioeconomic factors, then what is contributing to high rates of Black maternal and infant mortality in the US?

US healthcare’s systemic racism is well documented (Serena Williams experience, NPR/Pro Publica report)

US does not have comprehensive, equitable access to healthcare throughout pregnancy, let alone throughout a mother’s life cycle from childhood to elderhood

US does not have guaranteed meals for school-age children or equitable access to nutritious foods (vegetables or fruits)

All of this affects birth outcomes. Take a look below - factors beyond economic stability are summarized well.

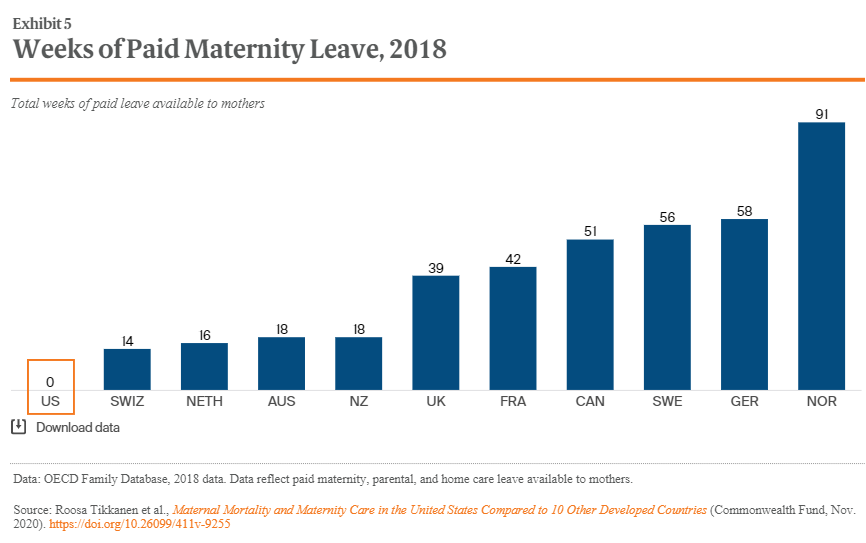

On paid maternity leave - do peer countries provide paid maternity leaves?

YES, they do.

Access to paid maternity leave is closely associated with better birth outcomes. A 2019 study reviewed California’s data after implementation of 2004 policy in support of paid family leave. Results: 12% reduction in postneonatal mortality after adjusting for maternal and neonatal factors.

compare rates of infant health outcomes before and after the implementation of the 2004 policy in California. The International Labour Organization (supported by UNICEF and WHO) clearly notes that maternity leave supports “women in coping with both the physiological and psychological demands of pregnancy, childbirth and breastfeeding. Paternity and parental leave are intended to provide support for the care and nurturing of children beyond childbirth, which should be shared by both fathers and mothers.”

And for paternity leave, US also ranks last per the UNICEF 2019 report.

Doesn’t Medicaid provide coverage for pregnancy?

Medicaid covers postpartum coverage for up to 60 days meaning that on day 61 in many states, mothers are potentially at risk of being unable to access healthcare. Under the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) of 2021, states were given the option to extend postpartum coverage to a full year, from April 1, 2022, for 5 years.

As of Feb 10 2023, only 29 states (including DC) have opted for the 12-month extension. While 6 other states were in the “planning” phase.

What about COVID-19 and the Families First Coronavirus Response Act?

During the public health emergency, the Families First Coronavirus Response Act allowed states to receive enhanced federal matching funds for Medicaid, IF, they provided continuous postpartum coverage to Medicaid enrollees. As a result, postpartum coverage has been continuous since the start of the coronavirus pandemic.

Since the anticipated ending of the public health emergency after May 11, 2023 - this provision is likely to also end. So, the American Rescue Plan Act can have a potentially greater effect on states looking to enhance Medicaid coverage for low-income mothers.

How many mothers would benefit if all states expanded Medicaid coverage to 1-year post-partum?

Expanding coverage to 1 year could prevent “prevent hundreds of thousands of enrollees from losing coverage in the months after delivery” as per KFF analysis.

Is one year enough for postpartum care?

NO. Most peer countries offer access to healthcare across the lifespan of a human being.

Nearly 30 million people in the United States are still uninsured,

and they are disproportionately people of color.

Final thoughts

The authors of the study summarize the factors that influence maternal mortality beautifully:

“Black infants and mothers may face disproportionate supply-side barriers within the healthcare system (e.g., due to financial incentives within the Medicaid managed care reimbursement system, as in Kuziemko et al., 2018), as well as demand-side barriers rooted in a long history of racism (Green et al., 2021; Green and Darity Jr, 2010).25 In addition, a large and persistent racial wealth gap in the US (Derenoncourt et al., 2022), policy induced racial segregation (Aaronson et al., 2020, 2021), racial disparities in pollution exposure (Currie et al., 2020b), and cumulative stress due to racial discrimination (Geronimus et al., 2006) are likely other important causes of poor health outcomes among Black Americans.”

I have colleagues who are mothers and they are Black. I cannot imagine going about my day without them - I depend on them as peers and friends. Knowing that they or their child are at risk because of the systemic lack of public policy guardrails in the US is unacceptable (to put it mildly).

We have to change the US policy and advocate for

Better access to care across the entire lifespan of a human being

Practicing evidence-based medicine for prenatal and postnatal care

Paid family leave

Ending systemic racism

Maternal health does not start at pregnancy.

It starts with healthy infanthood, food security and access to nutrition, clean water and air, neighborhoods free of violence and trauma, schools with advanced education and vocational training, families with paid family leave, and generations free of the anguish and harm from systemic racism.

It starts the moment a future mother is born.

The mother is the most precious possession of the nation, so precious that society advances its highest well-being when it protects the functions of the mother.”

- Ellen Key